I’ve had some pretty amazing wildlife encounters in my time, but I can safely say that all have been eclipsed by what I recently witnessed in Tahiti. This was an incredible trip, one that I hope to repeat again, even if it had a somewhat unfortunate ending.

Divers visiting Tahiti, typically do so for one reason. It is home to one of the world’s healthiest shark populations. At a time when sharks are being massacred globally on a scale that that has seen a reduction of 80% of all large shark species over the last 50 years and which sees over 100m sharks slaughtered each year, Tahiti has done an admiral job in protecting its marine life.

Although Tahiti enjoys a high degree of autonomy, it is still an overseas territory of France and the influence of France is all prevalent – from the French language which is universally spoken to the baguettes and croissants that are standard breakfast fare. Were it not for the coconut palms and the aqua marine lagoons, you could be forgiven for thinking that you were deep in Provence.

For developing countries, one of the positives of having a rich, developed nation as your benefactor is that they typically ensure good governance with a lid kept on corruption while the environment is usually well protected. Marine conservation tends to be non-existent or low down the totem pole in most developing countries and more often than not they have succumbed to short term monetary incentives offered by the likes of China and Taiwan who are anxious to gain access to the fish stocks of these nations. Once they gain entry, the impact, especially on the larger pelagic species, is nearly always rapid and devastating. Sharks are particularly vulnerable. Demand for their fins continues to grow as China becomes ever richer while supply is limited by the slow reproduction rates of sharks – the gestation period for many species is longer than that of humans.

Twenty years ago when I was first diving, it was possible to see abundant shark numbers in the waters of many Asian countries including Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines. Today the sharks in these waters are virtually gone. Other than the occasional migratory species, I sincerely doubt that there is even a single adult shark left in the South China Sea. Certainly, I have yet to see a shark in the offshore waters of Hong Kong and Southern China despite regularly being in the company of spear fisherman – usually a sure fire way of attracting sharks from a wide distance. Healthy shark populations are now confined almost exclusively to the waters of developed nations where there is adequate protection. Indeed, the majority of shark photos that one sees in today’s publications come from one small destination in the Northern Bahamas.

Anxious to avoid New Zealand’s Auckland airport, I chose to travel to Tahiti via Tokyo. Although this involves a bit of a detour coming from Hong Kong, Auckland has the world’s toughest hand luggage restrictions. As I always try to hand carry one underwater camera system as insurance against possible lost checked-in luggage, Auckland is top of my list of airports to avoid. Last year when I used the airport, something like 80% of passengers had their hand luggage weighed. Anything over 7kgs and you were forced to go back downstairs to the main check-in area. As far as I could tell, there were absolutely no exceptions to this rule and they would not tolerate any repacking of photo gear into the photo vest that I was wearing. Meanwhile, 300 lb Tongan passengers passed me at regular intervals. Were any of them weighed? Of course not. By contrast, the Hong Kong and Tokyo airports are a breeze and I had no problems with my 20+ kg hand luggage.

After a 12 hour overnight flight on Air Tahiti Nui (not bad), I arrived in the capital, Papeete, where I caught a 1 hour flight to the atoll of Rangiroa. In the late 80s and early 1990s, Rangiroa earned a reputation as one of world’s great shark diving destinations, famed for its “walls” of Grey Reef and Silvertip sharks. With expectations high, Rangiroa was however, a big letdown. While the currents were unfavourable on a number of dives – i.e. the currents were outgoing through the passes from the lagoon into the ocean creating poor water visibility – meaning that some of our dives had to be done away from the passes on the outside reefs, shark sightings were far and few between. I was told there were large numbers at 45-50 meters. However, even if one were to use a gas mixture of say 24-25% oxygen/75-76% nitrogen, the amount of time one could spend at such depths without making an extremely long decompression stop, would be limited. Moreover, when I checked with some other divers who had been down to these depths, I was told that yes, there were more sharks below 40m, although not huge numbers and more importantly, they were not coming close enough for acceptable photos. As a consequence, I didn’t bother making any of these deeper dives. The only highlight were several playful dolphins that showed up on a number of the dives.

And so after three days of average diving in Rangiroa, I headed for another, remoter atoll. Having been to this atoll last year, I knew what to expect and boy did it deliver.

Like Rangiroa, this atoll is roughly rectangular in shape and is composed of two narrow strips of land with a width of no more than a few hundred meters but a total length of 60kms. Encompassed within the atoll is a large lagoon with an area of over 1,100kms. The atoll is broken by two passes through which millions of gallons of water flow each day – typically there are two outgoing and incoming currents per day. It is in these passes that most of the marine life activity and behaviour take place.

The lagoon side of the island is spectacularly beautiful with breathtaking beaches and turquoise waters and, especially at the south end, is dotted with small, postcard perfect motus, or islands. The reefs on the lagoon side are ideal for snorkelling and are home to an abundance of small and large reef dwellers including this increasingly rare Napoleon Wrasse in the second image.

The reef side of the atoll is much wilder with high surf as a constant feature. The following image shows the reef side of the atoll at dusk on a day of high winds and intermittent rain.

I have noted that Tahiti is famed for its large shark population. But there is another, rarely seen marine event. It happens for only a few days each year, at a few select destinations in Tahiti. Unlike say the Sardine run off the coast of South Africa, it is an occurrence that is not well known by the diving community globally. This event is the massive spawning aggregations of Groupers and Surgeonfish.

Last year, by pure chance, I stumbled upon this event when I made a one day expedition to the more remote of the two passes. This year I made sure that I was based close to the pass so that I could dive it every day. The image below shows the lagoon at night and was taken outside my hut with the scene illuminated by a dazzlingly bright full moon.

Large numbers of Camouflage Groupers begin to gather five or six days before the full moon. In the days prior to the full moon, the Groupers are extremely placid and approachable to the extent that you can just about touch them. It is possible to lie down amongst them and have the fish swimming within a foot or two of you. Visibility tends to be good to excellent at this time.

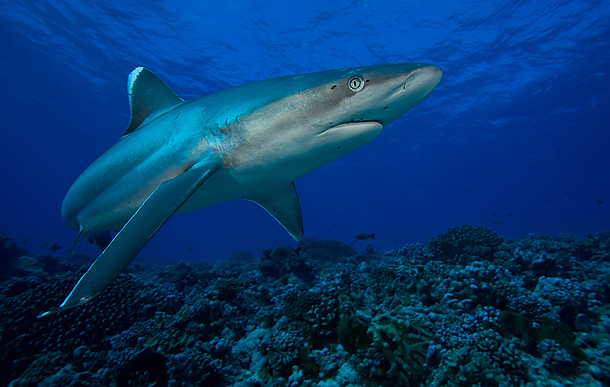

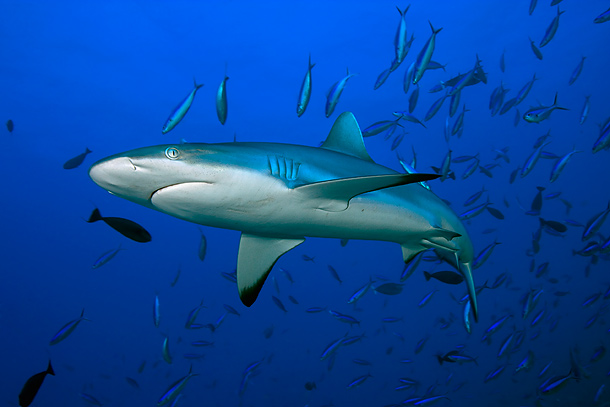

The Groupers come together in a location that is not far from a “Wall of Sharks” dive site. Literally hundreds of sharks – mainly Grey Reef, Silvertip and Pointed Nose Sharks patrol the wall, typically swimming into the current.

As the Groupers come together, some of these sharks will lazily make their way over to the aggregation, cruising amongst the fish but showing no signs of aggression. The Groupers appear completely unconcerned by the sharks and make only very languid movements to get out of the way.

As the day of the full moon approaches, the Grouper numbers increase. As far as the eye can see – and visibility is still a good 30m – Groupers blanket the bottom of the reef, at depths of 25-35m.

On the day of the full moon (the image below shows a full moon rising over a shallow lagoon on the reef side of the atoll), everything changes.

On my first morning dive, water visibility was down to a few meters -not because I was diving on an outgoing current, but because the water was thick with Grouper spawn. Gone was the placid behaviour exhibited by the Groupers on previous days. It was replaced instead by frenetic activity as groups of four or five Groupers would burst up from the reef floor, releasing their eggs in a thick milky cloud.

Meanwhile the spawning activity attracts large numbers of Grey Reef and Pointed Nose Sharks. Unlike the previous days when they showed little interest in the Groupers, they were now firmly fixated on catching and eating the Groupers. Unfortunately the sharks move so quickly that while you can see this activity, it is virtually impossible to catch with a still camera.

Joining the Groupers in the spawning frenzy were large numbers of Yellowfin Surgeonfish whose spawn clouded the water still further.

When I made my second dive later in the morning, the Grouper spawning had died down and the visibility had improved. However, there was a significant increase in Surgeonfish spawning activity. Not only was this continuing to draw sharks in prodigious numbers but large schools of Bluestreak Fusiliers were also attracted to the spawning commotion.

At no point did I ever feel concerned about the behaviour of the sharks. During the spawning they were very one-tracked with their focus exclusively on the spawning fish. Indeed both during the spawning and on the wall of sharks, getting close enough to the sharks was the main problem as they would tend to veer off when at a distance of 8-10 feet from me – close enough for most but for a photographer with wide angle lenses, there is no such thing as being too close to a shark.

I should note that because of the current changes, it is only possible to do two dives per day at this site and with peak activity at fairly deep depths and even allowing for the use of a 32% or 34% Nitrox mix, your bottom time at these depths isn’t more than 20-25 minutes. So adding up your two dives you only have 40-50 minutes to get your photos on the day of peak activity.

By the next day, the Groupers had completely ceased spawning. The Surgeonfish however, continued to spawn with attendant Fusiliers and Sharks.

By the following day all spawning had ended and most of the Groupers had vanished. At this stage I moved to the other Pass. If the currents are right, the North pass can have spectacular shark numbers and exciting drift dives, one of which culminates in a bowl shaped canyon where sizeable schools of Goatfish, Bigeyes, Soldierfish and Snappers gather. Nearby there are small caves with White Tip Reef Sharks, Snappers, Soldier and Squirrelfish.

On my second last day of diving, I made three fairly deep dives in strong currents. On the last dive, anxious to get a few last images , I lost the rest of the group on the ascent and safety stop. I surfaced some distance away from the dive tender but they eventually managed to locate me – I had stupidly left my orange safety sausage at the dive centre – a big no, no when diving in strong currents.

On the way back to shore, I noticed some soreness in the knuckle above my right forefinger. I didn’t think anything of it as I had experienced something similar on previous dive trips which I put down to muscle/joint fatigue from holding a camera for prolonged periods in strong currents – my underwater housing/strobes are negatively buoyant.

I went back to my accommodation, had a drink with some other divers (non-alcohol), grabbed some dinner and went to my room. After lying down for a few minutes, I thought I sensed a very minor numbness in my right foot. My right knuckle was still slightly sore. I now began to wonder if I had some mild decompression sickness, commonly known as “the bends”. When you dive, nitrogen enters the bloodstream. As you ascend, most of this nitrogen clears, but if you ascend too quickly or do not spend sufficient time at shallower depths to expel the nitrogen slowly, you can be left with nitrogen bubbles and/ or excess nitrogen in the bloodstream. For the last 15-20 years, computers (carried on the wrist) have been available to divers to ensure that they manage this process correctly. My dive profiles had been such that I had not exceeded no-decompression limits and I had made adequate safety stops on all dives but I began to wonder if I should have spent more time on the ascent at 15-10m or even if I should have done an even longer safety stop at 5m on the last dive given that the previous two dives had involved fairly extended periods at between 20-25m. I was also conscious that the surface interval between the 2nd and 3rd dive had been quite short (1 hour). I also remembered drinking very little water during the day and feeling quite tired between dives – these are also factors that more easily facilitate decompression sickness.

On the other hand, I had done many dives, especially early in my diving life with worse dive profiles and no ill consequences, and I should add that I have made close to 2,000 dives over the last 20 years and have never had any decompression issues.

For several minutes, I debated what to do. Was I just being paranoid? Decompression sickness can be a very serious condition resulting in paralysis or even death, but such eventualities are nearly always preceded by a diver making a very rapid ascent with immediate severe symptoms on the surface such as loss of consciousness, vomiting, dizziness, severe nausea, impaired motor functions etc. I did not have any of these. However, joint pain and numbness are secondary symptoms and I had these, albeit on a very minor scale. I admit to having a morbid fascination with decompression sickness and have read hundreds of case studies. When I talk with dive guides and dive boat captains, I always get around to asking them about their experiences with divers who have had decompression sickness.

Eventually, I concluded that it was better to be safe than sorry so I contacted my dive guide who came to collect me. We then made our way to a nearby clinic which by coincidence was run by his wife. As expected she immediately had me breathing oxygen. She then called the main hospital in the capital, Papeete (on another island). After a long conversation, in French, with a decompression sickness specialist, it was decided that it would be best if I receive immediate treatment in a decompression chamber at the hospital. This would mean that a plane would have to be sent for me to make the 1.5 hour journey to the main island.

Of course at this stage I could not help but think I had overreacted. I also felt a little embarrassed that a major operation was being launched on my behalf which might in fact be pointless. I asked the nurse if a medivac was really necessary but she replied that once the hospital specialist had made the decision, there was no turning back: “it is zee French protocol”.

After sticking an IV into my left arm, I then had one hour to pack up all my stuff. When it was determined that I would be flying out, two of the dive guides had gone to my room to retrieve all my gear. I had warned them that this in itself would be no easy task with bits of camera and underwater camera gear scattered all over my room. Commendably, they managed to get everything to me in several bags, but of course I needed to dismantle all the housings, strobes, arms etc. This required quite an effort given my restricted movement with the IV hanging out of my arm.

Five minutes after finishing (it was now 2am), we received word that the plane had arrived. Carrying the IV bag, the nurse drove me to the now deserted airstrip. I walked onto the small plane – just big enough for me to lie down and for a nurse and doctor to be seated. The flight passed uneventfully for the first hour at which point, I realised that I desperately needed to pee. Coupled with the water I had been guzzling, the IV fluids had filled my bladder to bursting point. Being a small plane, there was no bathroom on board, so what to do?

Fortunately or unfortunately, I had experienced a similar situation some years earlier when I had taken a three hour charter from Northern Australia to a remote location in Papua New Guinea. Travelling with two companions, we had consumed several beers prior to boarding. The resulting dilemma was solved as follows: one small plastic empty water bottle was located between the three of us. After one of us had finished, the pilot had to descend to lower altitudes and partially open one of the small side windows in the flight deck in order to empty the contents of the bottle. Not only was it necessary to perform this manoeuvre several times but as you can probably picture, some of the contents were blown back into the cabin. We had a good laugh afterwards although it was clear that when we landed the pilot did not share our sense of humour. Fortunately, there was no need to empty the bottle mid-flight this time and I managed the tricky exercise – kneeling down, back to the crew, IV still snaking out of my arm – without too much difficulty.

When the plane landed, an ambulance was waiting to whisk me to the nearby hospital. Within ten minutes I was in the cramped confines of the decompression chamber where I endured a three hour session with the compression in the chamber set at 18 meters. I say endured because although there was no discomfort relating to the pressure in the chamber, I had real trouble breathing from the oxygen mask that was clamped over my nose and mouth. I had to suck extremely hard to get a decent breath. I managed to get permission to loosen the mask very slightly which helped a little. But it was a long three hours and the discomfort with breathing made it impossible to sleep even though by the time the session ended it was 7am and I had had no sleep for the last 24 hours.

I should add at this stage that my symptoms – soreness in the knuckle of my right hand, slightly swollen and stiff fingers in the same hand and mild numbness in my right foot – were pretty much unchanged. This could mean either that the recompression process was having little or no effect (not uncommon with sensation type symptoms) or that in fact, I did not have decompression sickness.

After resting up in a hospital ward, I was back in the chamber six hours later for another two hour session, this time with the chamber set to 12m. Breathing was again an effort but I had bought a book this time to make the time pass a little quicker.

After spending the night in the hospital, my symptoms had dissipated considerably by the next morning with only some minor stiffness in my hand still evident. After being checked out by the medical staff I was told I was free to go. The main doctor noted that while he could not be certain, there was a good chance that I did not have decompression sickness. While my symptoms were consistent with decompression sickness, he said that in pretty much all cases where the symptoms were restricted to sensation ones, the soreness/stiffness/numbness would have been more widespread, e.g. down the whole of one’s right side.

I flew back to Hong Kong the next day with no incidents on the flights back. However, on waking on my first morning back in Hong Kong, I noticed that the top of my right arm and the lower part of my right leg were slightly numb. I went to a specialist the same day that put me through a whole series of motor and sensation tests. Everything turned out to be normal. As an additional precaution, I was sent for a brain MRI. Again, everything was normal (some relief to find out that I do indeed have a brain).

Since then my symptoms have almost disappeared. My hand and arm are now completely normal. The only symptom that I very occasionally experience is a minor tingling sensation in my right foot when I am sitting late at night. Hopefully this will pass with time.

Decompression sickness or not, the whole episode has certainly been a wake-up call to dive even more conservatively than before. Having had the dive profiles from my dive computer analysed, the conclusion was that while generally OK, I could probably afford to spend a little more time on the ascent at depths between 10-15m. In addition, I will be changing my Uwatech brand of dive computer to a Suunto one. I had noticed that while, for instance, my dive computer was telling me that I still had e.g. 5 minutes before exceeding no decompression limits, other divers on the same dive, who had been following a similar dive profile and who were using Suunto computers, were already five minutes into deco.

jattinn kochhar

August 2, 2010

Tahiti here i come.U r really gifted (with and without the camera)both ways.

c k su

August 3, 2010

I did not know sharks are so beautiful. Thanks

Michael Dickson

September 20, 2010

Beryl referred me to this blog. Your pics are amazing, and your way with words is no less impressive and entertaining.

Paul Mckenzie

September 21, 2010

Hi Michael,

Thank you for your generous comments. I still have some way to go on both fronts but hopefully I can keep improving.